This article is a continuation of my commentary on the politics of healthcare with particular focus on issues that likely interest those involved in market access and government relations. In this case, I’m commenting on government and market failure in healthcare.

A future article will present what I call a ‘reform pathway’ laying out some determinants of healthcare reform; this has relevance for country archetypes.

Let’s start with the notion of market failure. This is invoked by governments to justify intervention by way of rules, regulations to control perverse behaviours by market actors (e.g. cartels and competition law) or the formal intervention in the market itself (e.g. nationalisation, public corporations).

Countries, such as France, are called dirigiste because of the political belief that government, in some form, has a formal role to play in directing markets, so such a government will see a role as a market actor. This can have consequences, too. Government engagement in this way may stymie market reform, protect failing companies in which the government has (at least a golden) share, and justify self-serving (poor?) regulation. There is an old adage, that if you want regulatory reform, find a way to make the government subject to those regulations: they will very quickly be changed if they interfere with the government’s objectives.

I think an interesting example also in France concerns the drug benfluorex (Mediator) and which is in court litigation in 2019. The French state intervened on the regulatory side when it was learnt that the regulator had as the state saw it failed in its statutory duty. The current regulator, The Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament et des Produits de Santé (ANSM), took over the duties of Agence Française de Sécurité Sanitaire des Produits de Santé (AFSSAPS) on 1 May 2012.

In essence, the regulator at the time (AFSSAPS) had failed on a number of fronts, notably, tolerated the product on the market despite lacking therapeutic efficacy, inability to analyse the associated cardiotoxicity, was “rendered inefficient by bureaucratic processes and constrained by fear of legal disputes by companies. AFSSAPS’s failures were also attributed to its conflicts of interest and to industry influence over the agency”; this is called ‘regulatory capture’ and is a form of government failure; indeed it is no-one’s interests for regulators to fail in this way and indeed can lead to further strengthening of regulations.

A more general question would be to ask whether there is a risk of regulatory capture of medicines regulators and how would that manifest itself. There is published work on the subject, and I’ve included a couple of interest at the end, “Want to Know More?”

The Mediator case illustrates a crisis, and one in which the French state was forced to correct its own failure as AFSSAPS was a state-mandated regulator. The new regulator would, of course, seek to avoid the failures of its predecessor. Might one expect regulatory hyper-vigilance as a response? Perhaps the regulatory move on homeopathy is evidence as the French government announced that from 2021 it will no longer reimburse homeopathic treatment; given the long-standing evidence that homeopathy lacks efficacy, it is a case of better late than never though why it takes two years could be evidence of regulatory capture in the past.

Political and economic theories suggest that there are a number of factors that act to increase or decrease the role and size of government. The state as such is not compelled by these factors, but they do influence the decision making of key actors, and politicians usually follow political ideological lines.

The “critical legal” position is that the very distinction between the public and private sectors is broadly meaningless as from their perspective, no area of society is off-limits to intervention by the state. We can think of many areas where the state has intervened where it shouldn’t leading to perverse consequences, leading to review and even elimination of regulations or laws.

Neo-corporatists demand greater public supervision, regulation and oversight of the state. Evidence of market failure is on this view justification of more regulation. It is worth noting that government decides if there is market failure.

Bell and others have argued that the state in post-industrial societies has a particular interest in expanding into areas such as education, healthcare and research. How much the government should be involved is often a matter of ‘national taste’ but it does have an impact on overall welfare and the performance of labour markets. What this means for healthcare is understanding that there is a point at which the trade-offs become so dysfunctional that public sector reform is necessary to trim the size of the state, perhaps sustainability, perhaps digital disruption? In unpublished work I did for a government, I discerned that ‘unreformed’ departments of state were heavily staffed (measured as population per civil servant), with multiple agencies (some at arm’s length) and that the same functions could be performed with smaller staffing and fewer but better mandated agencies.

In the spirit of my own work, public choice theory shows that public spending and public bureaucracies expand to excessive and inefficient scale, and lead in many cases to government failure. A key element in public choice thinking is that public employees have an interest in increasing their own role and hence expand the role of their bureaucratic function; unsurprisingly, this is done by trying to maximise budgets at the expense of efficiency (it may be worth noting that this behaviour is found in corporations too).

As well, there is the continuing challenge of managing public expectations which have the effect of creating greater demand for the supply of government and regulation, such as more public services and higher public spending, think pot-holes, highways, class size, hospital waiting, or protect the public from dangerous medicines.

Taking these together, we can see that in a political understanding of market access, there is a dynamic tension to appreciate, between government failure and market failure. Let’s put that another way.

Government failure leads to calls for privatisation, central or public sector reform, and greater accountability and transparency. The public at large has very low tolerance for government failure since the government is seen as the ‘l ast resort’ and has no choice but to act, in the public interest. Examples include bailing out banks, protecting failing publicly funded hospitals from closing despite evidence of poor quality care. Compassionate prescribing is an example of the state as last resort for children with for example rare diseases to benefit from unlicensed or unapproved medicines, usually regardless of the cost and is a substitute for a regulatory solution which might fail HTA.

Market failure leads to things like call for nationalisation, and public ownership, along with more and one hopes better regulation, mindful that regulators are monopoly suppliers of regulation. By and large, the public has higher tolerance for market failure as in many cases there are options, people adapt, or the failure leads to new suppliers ‘disrupt’ failing markets with new products or services and thereby replace failing markets with ones that work better. The contrast with government failure is of course stark as one cannot forum shop for another government. Importantly, market failure that the public interest at risk does attract scrutiny and demand for action. And we are back at demands for greater supply of government.

Want to know more?

Bell G & Tawara N, The Size of Government and US/European Differences in Economic Performance, International Monetary Fund Working Paper, April 2009.

Borup R, Traulsen JM, Kaae S. Regulatory Capture in Pharmaceutical Policy Making: The Case of National Medicine Agencies Related to the EU Falsified Medicines Directive. Pharm Med. 2019;33(3):199-207.

Funnell W, Jupe R, Andrew J, In Government We Trust: Market Failure and the Delusions of Privatisation, Pluto Press, 2009.

Hood C, Keeping the Centre Small, Political Studies, 26:2006, 30-46.

Hunter D, Shishkin S, Taroni F, Steering the Purchaser: stewardship and government, in Josep Figueras, Ray Robinson, Elke Jakubowski (eds) Effective Purchasing for Health Gain, Open University, 2005.

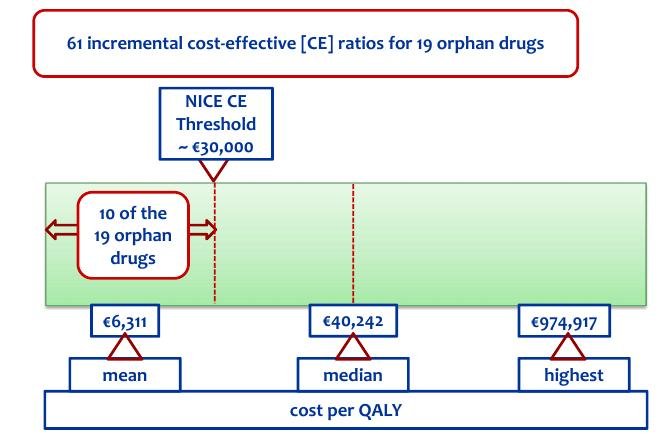

Picavet E, Cassiman D, Simoens S. What is known about the cost-effectiveness of orphan drugs? Evidence from cost-utility analyses. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 2015;(40(3)304-307. [source for the diagram]

Rémuzat C, Toumi M, Falissard B. New drug regulations in France: what are the impacts on market access? Part 1 – Overview of new drug regulations in France. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2013;1

Rémuzat C, Toumi M, Falissard B. New drug regulations in France: what are the impacts on market access? Part 2 – impacts on market access and impacts for the pharmaceutical industry. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2013;1.]

Venables V, Regulatory capture of the Food and Drug Administration as a result of new right neo-liberalism, BA Thesis, Washington College, 2016 (unpublished).